How to Write a Hypothesis: A Guide to Strong Writing

Hypotheses are one of the trickiest parts of academic writing, especially if you’re then expected to actually test them and report on your findings. If you don’t think you can do it on your own yet, it might be a good idea to turn to Essay Writers for help. Our experts will be happy to assist you with any writing task, including hypothesis writing. They’ve written thousands of research papers and know how to come up with a strong, testable hypothesis for any subject and topic.

However, with some guidance, you can absolutely nail hypothesis writing on your own. Just follow our tips – we’ll walk you through it.

What is a Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is your core research assumption in the form of a predictive statement. When you’re about to test something, you probably have an idea of what the test will show based on prior research and common sense. Simply put, a hypothesis is the projected result of your research.

Or, if you want a more technical definition of hypothesis, it’s a testable statement that predicts a relationship between the variables involved in your research.

For example, “Undergraduate students who received detailed written feedback (independent variable) will show more significant improvement in essay writing (dependent variable) over a semester compared to their peers who only receive a numerical grade.”

Common Types of Hypothesis in College-Level Research

This list isn’t complete, but here are some of the most common types you’ll see in college-level research:

- A null hypothesis assumes no relationship between the variables. Using our earlier example, the null hypothesis would be that detailed feedback doesn’t affect students’ writing skills.

- An alternative hypothesis is the opposite of the null hypothesis. It assumes a relationship between the variables.

- A directional hypothesis is similar to the alternative hypothesis, but it suggests not a relationship in general but a specific outcome of the research at hand. For example, giving detailed feedback to students will improve their writing skills.

- A non-directional hypothesis acknowledges a relationship but doesn’t predict the direction: “There is a difference in writing skills between students who receive detailed feedback vs. numerical grades.”

- A simple hypothesis involves only one independent and one dependent variable.

- A complex hypothesis involves multiple independent and/or dependent variables.

Of course, null, alternative, directional, and non-directional hypotheses can all be either simple or complex.

Hypothesis Examples of Different Types

Regardless of their type, the main function of all hypotheses is to clearly state an assumption you’re testing with your research. However, this doesn’t mean that your hypothesis has to be proven correct for it to be strong. Hypotheses are about making predictions that might turn out right or wrong. If your initial hypothesis doesn’t match the results of your research, this is perfectly fine (and quite common).

So, what should a good hypothesis look like? Here are a couple of examples for each type.

A few null hypothesis examples

- Studying in the morning vs. at night does not affect memory retention.

- There is no difference in the perceived stress level between people who walk 5,000 steps and those who walk 10,000 steps on average per day.

- Varying glucose concentrations have no effect on the rate of yeast respiration, as measured by carbon dioxide production (fl oz/min) over a 15-minute period.

Alternative hypothesis examples

- There are memory retention differences in students studying in the morning vs. at night.

- People who walk 5,000 steps and those who walk 10,000 steps on average per day report different stress levels.

- Varying glucose concentrations are associated with different rates of yeast respiration, as measured by carbon dioxide production (fl oz/min) over a 15-minute period.

Testable directional hypotheses

- Customers who engage with a company’s social media content will show higher levels of brand loyalty than those who do not.

- Patients checked on by nurses more frequently during their hospital stay will show higher levels of patient satisfaction.

- Laboratory mice exposed to higher ambient temperatures and a high-protein diet will have higher metabolic rates than mice kept at lower temperatures and fed a standard diet.

Strong non-directional hypotheses

- Customers who engage with a company’s social media content and those who do not will show different levels of brand loyalty.

- Patients’ satisfaction differs based on how often nurses check on them during their hospital stay, as measured by survey scores.

- Varying metabolic rates in laboratory mice are related to differences in ambient temperature and diet composition.

Effective simple hypothesis examples

- Students who practice mindfulness meditation for 10 minutes daily (independent variable) will report lower stress levels (dependent variable).

- Individuals who spend more than three hours per day on social media (independent variable) will report higher levels of loneliness (dependent variable).

- Customers who receive personalized promotional emails (independent variable) are more likely to make a purchase (dependent variable) than those who receive generic emails (comparison group).

Key Criteria for a Strong Hypothesis

As you can see from the examples, a hypothesis can belong to more than one type at once. For example, you might have a complex directional alternative hypothesis, a simple non-directional alternative hypothesis, a simple null hypothesis (as null hypotheses are almost always non-directional), etc. The type isn’t what makes a hypothesis strong or weak.

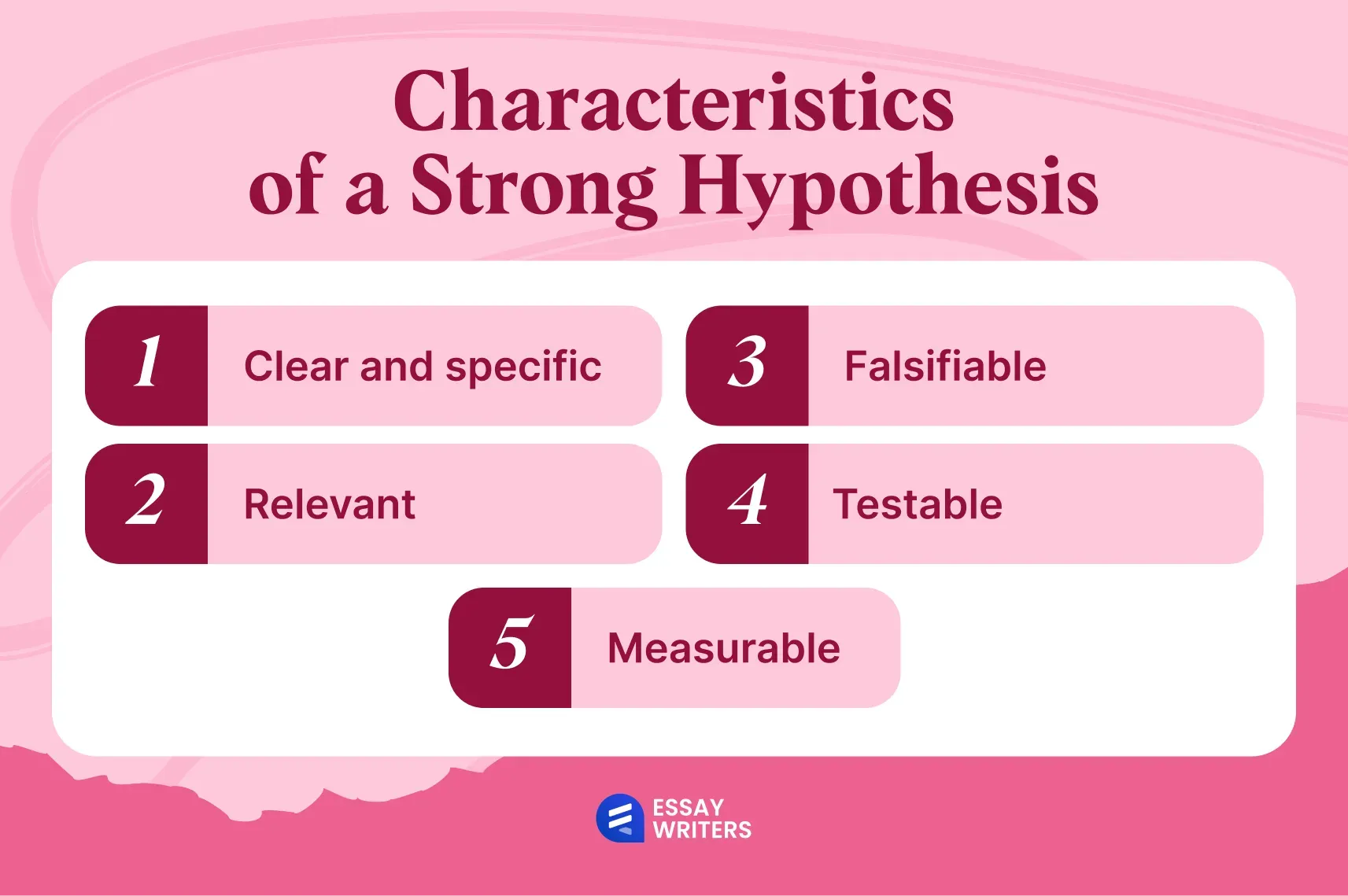

Then, what makes a good hypothesis? A good, strong hypothesis has to meet five main criteria: clarity, relevance, falsifiability, testability, and measurability.

It is clear and specific

First, a good hypothesis is clear and specific. This implies that your variables are clearly stated, and your audience doesn’t have to guess what it is exactly that you intend to test and hope to establish.

An example of a hypothesis that definitely does not meet this criterion is “Exercise affects health.” It’s unclear what your variables are and how you are going to measure the effects of exercise (what exercise?) on health (what does “health” imply).

It is relevant

Your hypothesis should also be relevant, meaning it should address a real research problem and contribute to knowledge in the field. Otherwise, what’s the point of even testing it?

For example, “Individuals who sleep less than 5 hours a night over two weeks will show cognitive decline as measured by standardized cognitive performance assessments” is not a relevant hypothesis. It’s a well-known fact by now.

It is falsifiable

Also, for a hypothesis to be good, it must be possible for it to be disproven. If you are 100% confident that your research will result in a certain outcome, it means that your hypothesis is either vague, unscientific, or a known fact that doesn’t need to be tested.

For instance, it would make sense to test things that are considered “universal truths” or “laws of nature” because the result of your research or experiment would be obvious in advance.

It is testable

A testable hypothesis is a hypothesis you can support or refute through observation, experiment, or data collection. Otherwise, what’s the point of your research?

That’s one of the reasons why quasi-scientific things like “internal energy” (e.g., “People with strong internal energy are more likely to succeed”) don’t belong in good hypotheses. How would you test something like that?

It is measurable

Finally, a good hypothesis must be measurable, meaning your variables must be defined in such a way that it’s possible to quantify or at least evaluate them.

An example of a non-measurable hypothesis would be, “Students who sleep well will score higher on memory tests than students who sleep badly.” “Well” and “badly” aren’t objective.

However, it can be reworked into a good, measurable hypothesis: “Students who sleep at least 7 hours per night will score higher on memory tests than students who sleep less than 7 hours.”

How to Write a Good Hypothesis

By now, you should have a general idea of how to write a hypothesis example for it to be effective. The type doesn’t matter much as long as your hypothesis is clear, relevant, falsifiable, testable, and measurable. A null hypothesis might be less exciting to test than an alternative one, but this doesn’t mean that all null hypotheses are inherently inadequate.

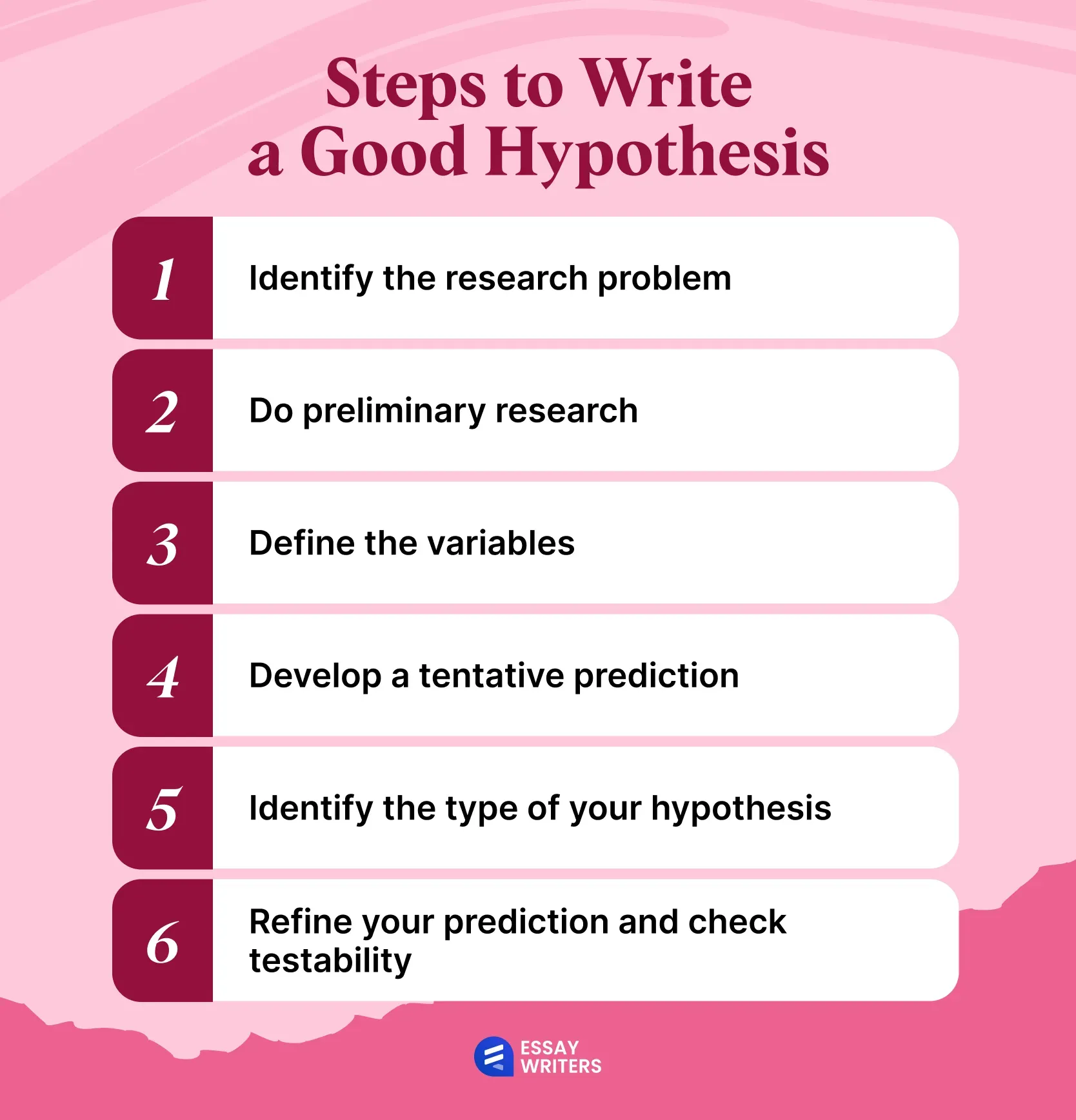

Still feel a little intimidated by the prospect of developing a hypothesis? If so, this step-by-step guide might help.

1. Identify the research problem

How to start a hypothesis? First, you’ll need to find a question you’d like to answer with your research. Ideally, it should be something you’re actually interested in. Otherwise, you’ll find the research process boring, and this might affect the quality.

Also, it’s better to choose something that isn’t over-researched. You’ll be way more excited about your study if you don’t know the answer to it in advance, just from reading relevant literature.

2. Do preliminary research

Next, research the problem you’re planning to explore. Read relevant studies to understand what is already known and identify gaps. If you are developing a hypothesis for a study at school, your professor will typically expect you to try to fill in a gap in current literature, not just retest something that has already been tested a thousand times.

3. Define the variables

One of the most important steps in forming a hypothesis is defining your variables. You need to identify the independent variable (what you manipulate) and the dependent variable (what you measure). Make sure you don’t confuse the two. It’s a pretty common mistake among students.

Just remember that the thing you’re measuring is always your dependent variable. For example, sleep quality in active social media users is the dependent variable, and the amount of time they spend on social media is the independent variable.

4. Develop a tentative prediction

Now, you can try to formulate your hypothesis, although you need to be prepared to revise or completely reformulate it later on. All you need to do here is write a clear, testable prediction about the relationship between the variables.

You might find this formula helpful:

“If [independent variable] is [manipulated or changed in some way], then [dependent variable] will [expected effect or outcome].”

5. Identify the type of your hypothesis

Now, try to determine if your hypothesis will be null or alternative, directional or non-directional, and simple or complex. It’s perfectly fine if, when writing a hypothesis, you didn’t think about the type. In fact, it’s better.

Remember that the type of your hypothesis doesn’t affect its quality. Just look at your preliminary research and the variables you defined and decide which type fits best.

6. Refine your prediction and check testability

Finally, you can formulate your final hypothesis. But first, triple-check that it meets all the key criteria we’ve just discussed. Make sure that your hypothesis is specific, measurable, and falsifiable, or else it won’t be any good.

Once you’re confident that you’re good to go, revise for clarity one final time. It helps to show your hypothesis to a few people so they can confirm that it’s clear what you intend to test and how.

Conclusion

Writing a hypothesis for the first time can be scary. But we promise you that with all the information you now have, you can absolutely nail it. Just keep the five most important criteria in mind: clarity, relevance, falsifiability, testability, and measurability. As long as your hypothesis meets all of them, it’s great.

Also, you can use this checklist every time you need to remember how to write a proper hypothesis:

- Have I identified my variables correctly?

- Is my hypothesis clear, relevant, falsifiable, testable, and measurable?

- Does the research I plan to conduct actually fill a gap in knowledge?

- Does my hypothesis express the focus of my study accurately?

If your answer is a confident yes to all of these, you have every reason to be proud of your hypothesis.

And remember, if you struggle with your hypothesis or any other academic task, you can always order a paper from experts. We are here for you and will happily help you with absolutely any assignment.

FAQs

Is a hypothesis a question?

A hypothesis can be formulated as a question, but it’s typically not, at least not in academic settings. Instead, it’s a predictive statement that you’re going to test. There is an implicit question in it that you are trying to answer, but the statement itself isn’t worded as a question.

What is a basic hypothesis structure?

The structure of a hypothesis depends on its type. A null hypothesis is different from an alternative one, and a directional hypothesis isn’t structured the same as a non-directional one. However, the most basic formula for a hypothesis is, “If [independent variable] is [manipulated or changed in some way], then [dependent variable] will [expected effect or outcome].”

How to form a hypothesis?

To form a hypothesis, you need to do preliminary research, identify a research gap you’d like to fill, form a tentative predictive statement, and then revise it to formulate your hypothesis. When finalizing your hypothesis, make sure it meets the five key criteria: clarity, relevance, falsifiability, testability, and measurability.