How to write

Short Essay Examples: A Complete Guide for Students

Author: Michael Perkins

Jan 6, 2026

min

Table of contents

A short essay is a focused piece of writing, usually between 200 and 500 words, built around a clear introduction, two or three concise body paragraphs, and a brief conclusion. Despite the smaller word count, it follows the same structure as longer essays.

At EssayWriters.com, you can explore short essay examples for students, strengthen writing skills, and learn how to make every word count. Our authors help you prepare essays that stand out and reflect your understanding of key ideas within a limited space.

What Is a Short Essay?

A short essay is a concise piece of writing, usually between 200 and 500 words, that presents a single idea or argument clearly and logically. This short essay length allows writers to focus on one central point while following a simple structure with an introduction, body, and conclusion. These essays are often used for exams and assignments. Additionally, many colleges ask for short papers as part of the admissions process.

Why You Should Write Short Essays

When writing your short essay during a school year, you’re working with a tight word limit, barely a few hundred words, but inside that small space, you learn how each line has to do something. Some add value, others move the idea forward. And before you know it, you’ve said more than you thought possible. Here’s why you should write short essays:

- Clear communication: There’s no fluff or detours in short essays. You learn how to build meaning with fewer words, how to sound confident without dressing it up. It’s a skill that feels awkward at first; you cut more than you write, but clarity grows out of that friction. Writing this way teaches you what matters and what doesn’t.

- Critical thinking: Every sentence competes for space, so you start asking sharper questions: Does this detail move my point forward? Does it even belong here? The more you practice, the faster you see connections between thoughts. It’s a kind of mental editing that sticks with you.

- Building writing confidence: Every short essay is a new round of trial and error. Some flow, some don’t. You rewrite sentences, shift ideas, change tone halfway through, and that’s how you grow. You start trusting your rhythm, those tiny hesitations before a word lands just right. The process stops feeling like writing an essay and starts feeling like talking, only sharper.

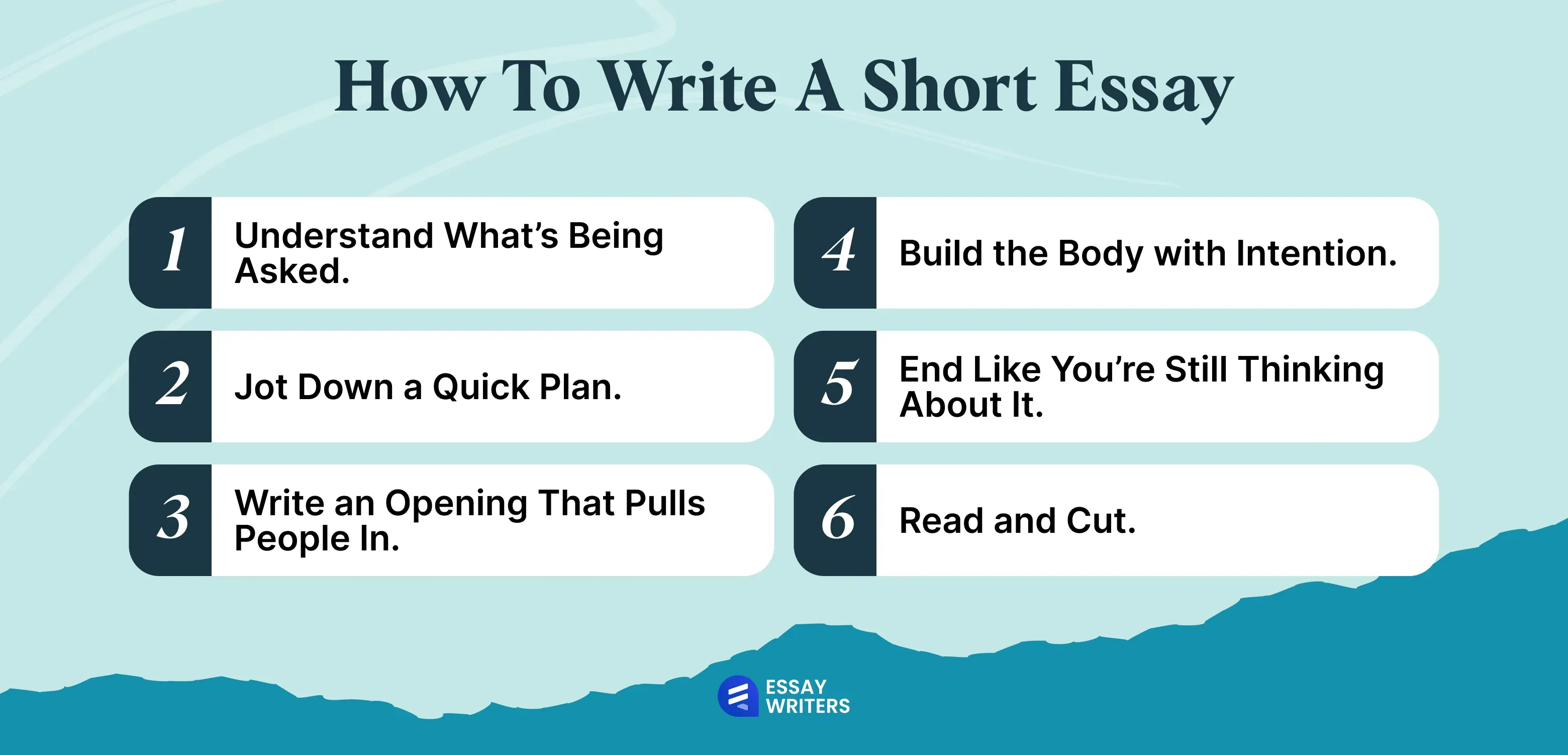

How to Write a Short Essay?

Writing a short essay is about learning how to say something meaningful without wasting space. To reach that clarity, you first need to understand the question, plan your thoughts, write a strong opening, develop concise paragraphs, and close with a meaningful reflection before refining every line through editing. Below, we’ll walk you through the necessary steps to write a short essay.

Step 1: Analyze the Essay Prompt

Read the prompt carefully, maybe even out loud. Most students skim once, then jump straight in, but short college essays don’t allow impatience. You have to know exactly what the question asks before you start figuring out an answer.

If the topic is 'Should schools limit social media access?', don’t take the bait and write about all of social media. Zoom in. Maybe you can explore how constant scrolling affects concentration or how school rules could teach digital balance. Narrowing the focus means less clutter and more clarity.

Step 2: Create a Writing Plan

Scribble notes in the margin, write key phrases, maybe even a few half-formed sentences. The point is to see the shape of your idea before you start tightening it.

You might find your main point changing halfway through, and that’s fine. Short essays shift as you write; sometimes, the real idea only shows up in the middle of a paragraph. That’s part of the process.

Step 3: Write an Engaging Opening

The first line sets everything in motion. It doesn’t need to be brilliant; it just needs to sound human. Start with something that feels alive, such as a question or a flicker of surprise.

Example: Most people think focus means working harder, but it really starts with knowing when to stop.

Then slide into your thesis, something clean and sure of itself: Schools should limit social media use during class hours to help students rebuild real attention spans. That’s your anchor. Every line that follows should pull back toward it.

And if you ever get stuck on phrasing, the argumentative essay writing service at EssayWriters can help shape your draft into something crisp.

Step 4: Develop the Focused Body Paragraph

Each paragraph should hold one idea, maybe two if they’re close. Begin with a sentence that says what this part is about. Then give an example, a stat, or a thought, something that proves it’s worth reading.

Example: Students who check their phones every ten minutes spend nearly twice as long completing assignments as those who don’t.

You don’t need to explain every detail. Let one strong image or fact carry the meaning.

Step 5: End with Insight and Reflection

A short essay doesn’t need a grand finale. It just needs a closing thought that feels genuine. Circle back to your thesis, but show you’ve traveled somewhere new.

Example: Maybe the problem isn’t social media itself, but how easily we forget what focus feels like.

It’s a reflection, not a summary.

Step 6: Revise and Refine

Editing short essays is oddly satisfying. You see how every small change makes the whole piece cleaner. Read it aloud and notice the rhythm. If a sentence feels stiff, break it. If something repeats, decide if it adds rhythm or just noise.

Also worth reading: Business essay format

Short Essay Examples

The best way to learn how to write is to see it done. Each short essay sample below shows how structure, tone, and focus work together when there’s little space to waste.

Example 1: The Emotional Weight of Unfinished To-Do Lists

An unfinished to-do list often holds more than incomplete work; it carries a quiet sense of failure that can last beyond the day. What begins as a tool for order can become a measure of worth. Each unchecked box seems to judge not only productivity but also discipline and self-control that apply to everyday lives.

The pressure builds with expectation. People plan their days believing that completion will bring relief or satisfaction. When tasks remain undone, the opposite happens. Psychologists call this the Zeigarnik effect, the brain’s tendency to dwell on unfinished business. This mental tension can feel like guilt, even when the delay is reasonable. In a culture that treats constant productivity as success, incompletion feels unacceptable.

Emotionally, the list turns into something heavier. It stops being a guide and becomes proof of falling behind. Yet the weight can teach something valuable. It shows the gap between ambition and what time allows. Learning to accept unfinished work without shame is part of finding balance.

A to-do list should direct focus, not define identity. Leaving boxes empty does not erase effort. It reminds us that being human includes limits, and that some days, rest or reflection matters as much as crossing another task off.

Example 2: Why Students Multitask Even When They Know It Does Not Work

Many students multitask, knowing it slows them down, yet they keep doing it. It is not a lack of awareness but a mix of habit, pressure, and distraction. Modern learning demands attention from every direction, like messages, deadlines, and constant notifications, so dividing focus feels natural, even productive.

The illusion begins with control. Switching between screens gives a sense of efficiency, as though progress multiplies with every open tab. In reality, cognitive research shows the opposite. The brain does not perform two demanding tasks at once; it simply shifts rapidly, losing time and depth with each move. This constant switching creates mental fatigue and fragments understanding, leaving students busy but not truly engaged.

Still, multitasking satisfies something emotional. It eases the discomfort of monotony. It offers the feeling of movement, even when the work stands still. For many students, silence feels heavier than distraction; being busy, even inefficiently, seems better than facing stillness.

The persistence of multitasking reflects more than poor study habits. It mirrors a culture that rewards speed over focus. Learning to stay with one task, without the noise of three others waiting, is a small act of resistance in a world built to divide attention.

Example 3: The Performative Kindness of Social Media 'Support'

Online kindness often looks generous on the surface. A heart emoji, a comment that says 'You’ve got this,' or a short post about empathy can appear like real care. Yet behind much of this activity lies something thinner: support performed for visibility more than connection. People want to be seen as being kind, and that subtle shift changes everything.

Social media rewards appearance. Every like or repost signals approval, so kindness becomes a way to participate rather than a means of genuine help. A user writes 'sending love' to a friend they have not spoken to in years, or reposts a story about mental health without reading beyond the headline. It feels like a contribution, and in a digital sense, it is. But it is also safe. No conversation, no discomfort, no real effort.

Still, this kind of public empathy is not meaningless. Sometimes it starts something: a reminder, a nudge, a bridge between silence and dialogue. Yet when support becomes habitually shallow, it dulls the meaning of care itself. The gesture remains, but the substance fades. True kindness still happens quietly, away from screens, where there is no audience to measure it. It asks for time, not clicks.

Example 4: Why People Keep Playlists for Certain Seasons

Music follows the weather more than most people admit. Playlists form around seasons almost naturally, like memories arranging themselves by sound. Summer songs feel loud and loose, filled with sunlight and open windows. Winter music softens, with slower tempos, quieter voices, songs that sound like reflection. The shift is less about taste and more about mood, as if each season speaks a different emotional language.

People return to the same playlists year after year because they hold more than tracks. They store time. A song that once played during long walks in spring carries that light forever. The same tune, heard in autumn, feels like remembering rather than living. These patterns are rarely deliberate. They form as weather changes, as people move through the same routines under different skies.

Playlists become a kind of emotional calendar. They remind listeners who they were the last time that song played on repeat. Maybe a friend was still around, or a certain goal still felt possible. The music does not change, but the listener does. Keeping seasonal playlists is not only about sound; it is a quiet way of marking time, holding memories in rhythm until the next cycle begins.

Example 5: What We Trade When We Trade Privacy for Convenience

Every new app promises ease: faster orders, smarter suggestions, fewer clicks. The trade feels harmless at first. You give up a little information in exchange for time. However, over time, those small exchanges accumulate until privacy becomes another invisible cost of modern convenience.

People rarely notice the shift. A quick face scan to unlock a phone, location tracking to find a nearby café, and automatic logins that remember passwords; each act saves a few seconds. Yet with every convenience, a fragment of personal data leaves the person who created it. Algorithms learn patterns, predict desires, and build quiet profiles that shape what appears next. The control moves elsewhere, slowly, almost politely.

The strange part is that most people know this. They click 'accept'. Comfort wins. Convenience feels tangible; privacy does not. Losing a bit of data does not sting in the moment; it only echoes later, when ads seem to read thoughts or devices finish sentences.

This trade-off defines the digital age: a world where freedom feels like efficiency, and where ease hides its own price. Protecting privacy now requires intention, a small act of resistance against the smoothness of systems designed to make thinking optional.

The Bottom Line

Short essays may be brief, but they teach powerful lessons in clarity and precision. With limited space, you learn to focus on what truly matters and cut everything else. This practice builds sharper thinking, stronger arguments, and clear communication under pressure.

If you want to develop that skill further, EssayWriters can help. You can work with experts who plan, structure, and edit your essays effectively, whether it’s a reflection, analysis, or a paper on topics like Different Research Methods in Psychology.

FAQs

What Does a Short Essay Look Like?

A short essay has a similar structure to any other academic piece of writing. It consists of an introduction, body paragraph(s), and a conclusion.

Is 300 Words a Short Essay?

Yes, a 300-word essay is considered a short one. It allows you to introduce your topic, support it with body paragraph(s), and close with a concise statement.

How Long Is a Short Essay?

A short essay length ranges from 200 to 500 words, depending on the topic and your professor’s requirements. The focus should always be on presenting one central idea rather than covering multiple ones.

How Many Paragraphs Is a Short Essay?

A short essay usually has three to five paragraphs: one for the introduction, up to three for the main body, and one for the conclusion.

How Many Sentences Is a Short Essay?

A short essay typically consists of around 15 to 25 sentences, which is sufficient to explore one idea with clarity and provide it room to breathe without overwhelming the reader.

Sources

- University of Oxford. (n.d.). Essay writing. University of Oxford. https://www.ox.ac.uk/students/academic/guidance/skills/essay

- University of Auckland. (n.d.). Essay writing. Learning Essentials. https://learningessentials.auckland.ac.nz/writing-effectively/assignment-types/essay/

- University of Evansville. (n.d.). Parts of an essay. Writing Center. https://www.evansville.edu/writingcenter/downloads/parts.pdf